NEWS & VIEWS

Tax Talk is a regular series written by FSL’s tax expert, Alex Ranahan. Alex has nearly ten years’ experience as a tax adviser and analyst. He is accredited by The Association of Taxation Technicians and was recently elected co-chair of the Tax Committee for The Investing and Saving Alliance.

Alex’s Tax Talks are on general topics and are not tax or financial advice. If you are unsure of the tax treatment of a transaction, we encourage you to seek the appropriate tax advice.

After a long 2020 and 2021, with the deadliest pandemic in a century, and amid the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Finance Act 2022 (FA22) aimed to encourage economic recovery. But work is already underway on the Finance Act 2023 (FA23), and on 20 July HMRC published the draft legislation and accompanying notes.

Much has already been done on tax issues, whether by consultation or review, but recommendations were not implemented in time for FA22. Publication of the Finance Bill 2022-23 (the name for the act as it goes through parliament) is a starting pistol for recommendations to be taken up. Probably the most consequential legislation deals with CGT on transfers of assets between spouses and civil partners who are in the process of separating. This recommendation was given in the Office of Tax Simplification’s second report and was accepted by HMRC in their response. So what changed?

CGT and transfers between spouses

Let’s look first at the current rule. And please note where this article refers to spouses it should be taken to include civil partners.

As you may already know, transfers between spouses are made at ‘no gain no loss’. This is one of the most valuable CGT treatments in the tax code as it means that if one spouse pays more tax than the other, the couple can take advantage of two annual exemptions and two basic rate bands to reduce their household tax bill. This treatment is only available to a married couple who live together at any time in the tax year. If a couple separates, any transfers between them are only made at no gain no loss until the end of that tax year. From the following 6th April, transfers are instead made at market value – because spouses are ‘connected persons’ – and CGT may be payable by the transferor on any capital gain. Transfers are made at market value until the date of the decree absolute, when the divorce is legally completed, from which point all transfers are treated as normal disposals at arm’s length.

The issue is with that second phase, when a couple is separated but not yet divorced. As you can see, they have only until the end of the tax year in which they separate to enjoy tax-free – and stress-free – transfers. This period could be as long as a year if they separate on 10th April, but could be as short as a few days if they separate on 31st March. And a couple undergoing a separation is unlikely to be in the frame of mind to allocate all their assets to one another before that favourable treatment expires.

The draft legislation extends this period of tax-free transfers. Couples will have three years from the end of the tax year they separate to make any transfers at no gain no loss. So, for example, a couple who separate on 1st June 2022 will have not just until 5th April 2023 but until 5th April 2026 – or until the date their divorce completes, whichever is sooner.

Whilst the draft rule allows separations which have taken place before 2023/24 to enjoy this extension, the no gain no loss treatment will only apply to transfers which have taken place on or after 6th April 2023.

Private residence relief

The other extension of relief for divorcing spouses is in private residence relief (PPR). This is the relief you get when you sell your main home so that you don’t end up with a large tax bill on top of all the other stress of moving home.

The current rule is that spouses may only have one main residence between them whilst they live together. Otherwise someone who sold rental properties would never pay tax on their profits, for example.

As with the no gain no loss transfers we talked about earlier, this creates a problem during the period when the couple is separated but before their divorce is finalised. Typically, one spouse will move out of the family home while the other will stay. Currently, the spouse who moves out will only get relief on disposing of their share of the home if they transfer it to the spouse who stayed put or if there is a court order which stipulates how to deal with the family home – a ‘mesher order’.

As I hope you can see, this means whichever spouse moves out of the home is quite disadvantaged. They might only be able to claim full relief if they sell their part of the home back to the spouse they have just separated from. I’m sure I don’t need to list the reasons why a couple whose marriage has broken down might be unwilling to discuss tax and financial matters with one another. The draft legislation is a welcome extension to the rule. The person who has left the home will be able to dispose of their ownership of the home to any person, not just their former partner, and enjoy full tax relief. Alternatively, if they transfer their share of the home to the spouse who is staying and, when the house is eventually sold, receive their share of the proceeds, then they will again get relief on the proceeds.

Relief at source

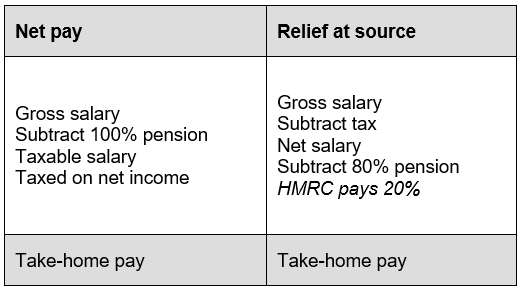

The other personal tax area covered is the correction of the quirk in tax relief for pension contributions made by lower earners to a ‘net pay’ scheme. Broadly, there are two types of workplace pension scheme: ‘net pay’ and ‘relief at source.’ There are also ‘salary sacrifice’ arrangements but they are not relevant here.

An employee whose pension contributions are made under relief at source arrangements knows that HMRC will always top up their contributions. This happens whatever the level of tax the employee pays even if the employee does not earn enough income to pay any Income Tax at all.

Following the order I set out above, you can see that this means the low earner is effectively making their contribution from gross pay under relief at source because they do not have any tax to subtract. The low earner is effectively getting an additional contribution to their pension pot. By contrast, a low earner whose pension is net pay does not get a top-up. This puts them at an obvious disadvantage as in order to put the same amount into their pension pot they need to fork out more of their income. The draft legislation corrects this by requiring HMRC to top up the pension pot of a low earner whose pension contributions are made under net pay arrangements. This ensures that equal tax relief is offered under both pension arrangements.

Overall, the draft finance act has few significant changes so far. However, given that we now have a new Prime Minister and Chancellor, and a huge set of political and economic challenges to tackle, I certainly won’t bet against further changes any time soon.